最上義光歴史館

|

The Death of Mitsukane

After the battle of Mount Kashiwagi, Lord Yoshiaki summoned Ujiie Owari no Kami and Irago Sōgyū. “We are fortunate indeed that the battle has ended and Terumune has withdrawn,” his lordship said, “but is this not the ideal opportunity for us to press on towards Kaminoyama and put an end to Mitsukane? The Kaminoyama force was badly routed at the battle of Mount Kashiwagi, and the loss of Terumune has them disheartened. They have lost their nerve, and it should be easy enough to take them on now.” Ujiie moved forward and spoke. “Your lordship has spoken truly. However, among Mitsukane’s long-serving vassals are Satomi Kuranosuke, Satomi Minbu, and Satomi Echigo – three warriors well-known for their exceptional valor – and among even the ordinary soldiers there are many who have distinguished themselves with manifold feats of heroism, so we cannot expect to overcome the Kaminoyama garrison easily. If enough time passes, Lord Terumune will undoubtedly come to Mitsukane’s aid once again, and this would complicate things for us. I believe that our best option in this case is to employ a scheme that will allow us to take Mitsukane down without the use of military force. There is a man who can help us carry out such a plan – a priest who is the younger brother of one of my most trusted vassals. He maintains a temple in Kaminoyama and is in the habit of frequenting Kuranosuke and Minbu, and when I have asked him in confidence to tell me about the character of these two men, he says that while the elder brother Kuranosuke is a model of unswerving rectitude, the younger brother Minbu – although certainly possessed of skills in battle the likes of which are seldom seem – is a man more interested in furthering his position in the world. If we approach him with a letter that promises him a generous fiefdom, he should not hesitate to join us, and with Minbu on our side, it will be easy enough to deal with Mitsukane.” “It is a wise plan,” said Lord Yoshiaki upon hearing Ujiie’s proposal. “Let us first use this priest to gauge the interest of the Satomi brothers, and we can dispatch a letter subsequently.” “Owari no Kami has proposed a most excellent strategy,” Sōgyū concurred, “one that should bring us success without overmuch difficulty.” With Sōgyū’s approval, Lord Yoshiaki was all the more convinced of the merits of this plan. With the matter thus settled, Owari no Kami summoned the aforementioned priest. With Sōgyū, he carefully instructed the priest in what he was to do, and then instructed him to proceed to Kaminoyama. As the priest was in the habit of associating with the Satomi brothers on a regular basis, he had come to be on friendly terms with them, and the two brothers would often engage him in conversation. One day, the priest spoke to Kuranosuke as follows: “As you know, my elder brother is in the service of Ujiie Owari no Kami, and yesterday, a messenger arrived with news from him that Lord Yoshiaki intends to make an assault upon Kaminoyama. As this will throw the region into turmoil, he warned that ordinary folk like myself should prepare ourselves for this eventuality. Until now, Mitsukane had always turned to Lord Terumune of Sendai in his hour of need, but with the accord that was struck between Lord Yoshiaki and Lord Terumune after the recent battle of Mount Kashiwagi, there are no longer any allies to help defend Kaminoyama if it comes under attack, and the castle is sure to fall. If this were to happen, it would no doubt mean the end of the Satomi clan as well, which would be a most grievous turn of events. Would it not be wise to make arrangements to avoid such a possibility before the enemy arrives?” Kuranosuke listened closely to the priest’s words. “As you have said, it is true that Lord Yoshiaki has been reconciled with Lord Terumune of Sendai, and we now have no allies to come to our aid. In addition, our castle does not have the capacity to withstand the assault of a large force, and it would no doubt fall in a matter of days. However, it would be most ignoble of a warrior to desert the master his family has served for long generations in an attempt to save his own skin. For me, there is no road left but to prepare to die in defense of my duty.” Realizing that there was little chance of convincing a man such as Kuranosuke to change sides, the priest decided to push the matter no further, instead electing to pay a visit to Minbu at the next possible opportunity. He repeated to Minbu that which he had said to Kuranosuke, but unlike Kuranosuke, Minbu did not hesitate to air his grievances over the situation. “Pitted against the great army of Lord Yoshiaki,” he said, “the small force defending Kaminoyama would fall before the end of a single day. Even if Lord Terumune were still willing to come to our aid, we are a considerable distance from his domain, and there would be little he could do for us in the event of a sudden attack. And now that he has allied himself with Lord Yoshiaki, the downfall of the Kaminoyama clan is surely but a matter of time. What is more, Lord Yoshiaki is renowned as a leader who embodies the three virtues of wisdom, benevolence, and courage, and none of the lords of this region would dare challenge him. Knowing this, I have repeatedly urged Mitsukane to submit to Yoshiaki’s rule, but he has consistently refused to listen. To die in vain for such a master would be a humiliating end, but if I were instead to establish myself as an ally of Lord Yoshiaki – which would allow me to raise the reputation of my family and do honor to my ancestors – there would still be none who called me faithful, but instead a dishonorable man who gave himself to the enemy. This too would be unbearable, and there seems no resolution to the predicament in which I find myself.” Minbu unburdened himself in great detail to the priest, who was pleased at what he heard. “Even if Lord Mitsukane is fated to meet his ruin because he fails to heed your counsel,” the priest said, “the perpetuation of the noble Satomi clan would be a source of comfort to all, including ordinary folk like myself. I hope that you will give your options much careful consideration.” With this, the priest took his leave of Minbu. The priest then made his way to Yamagata, where he met with Ujiie Owari no Kami and recounted all that had passed. Owari no Kami received this news with great pleasure, and, leaving the priest at his home, he went forth with Sōgyū to present himself before Lord Yoshiaki. Given a detailed account of the sentiments of the Satomi brothers, his lordship was in no small measure gratified, and he immediately summoned the priest and presented him with ten silver coins as a preliminary reward. His lordship then penned Minbu a courteous letter in his own hand and entrusted it to the priest, who proceeded with all haste to Minbu’s residence. There he spoke to Minbu, saying, “When I informed Owari no Kami in confidence of the matter of which we spoke recently, Lord Yoshiaki, who has heard tell of your valor in battle, was most pleased, and he bade me immediately bring you a letter written in his own hand.” The priest drew out the scroll containing Lord Yoshiaki’s message and handed it to Minbu, who reverently raised the epistle thrice to his head. He then unrolled the scroll to read the message, which ran as follows: “In response to Mitsukane’s attempted act of treason against myself, I have raised an army to exact vengeance upon him. I do not welcome the thought, however, of the ordinary folk of the region being forced to flee their habitations to avoid a battle, and it was as I was considering my path forward that I came to hear of your true feelings towards Mitsukane, news that I welcome with great pleasure. If you will prove yourself a faithful servant to me by slaying Mitsukane forthwith, I will confer upon you the territory ruled by Mitsukane in its entirety.” Minbu rolled up the letter after he had finished his perusal, and he turned to the priest. “It is you alone I have to thank for acquainting Lord Yoshiaki with that which lies within my heart, and for conveying to me this letter in his lordship’s own hand,” he said, presenting the priest with ten rolls of white cloth as a measure of his gratitude. “I will inform my brother Kuranosuke of what I intend to do,” he continued, “and if he refuses to fall in with me, I will slay him with my sword, and then I will kill Mitsukane. To offer me counsel in this endeavor, I hope that Lord Yoshiaki will see fit to dispatch to my side one of his trusted retainers.” The priest returned to Yamagata with Minbu’s request, to which Lord Yoshiaki readily acquiesced. His lordship summoned Yagashiwa Sagami no Kami, who was the son-in-law of Owari no Kami, and explained to him his commission. “Go forth to Kaminoyama and give Minbu the counsel he requires,” his lordship said. “If Mitsukane should happen to hear of Minbu’s defection and attempt to flee, maintain contact with Minbu, and wherever Mitsukane may go, make sure that you find and kill him. We must not allow your true purpose to come to light before this matter is brought to a successful resolution, so let it be known to your associates that you travel to Kaminoyama to treat your ills in the healing waters of the hot springs there.” Sagami no Kami accepted the assignment given him, and, speaking of the matter only with Owari no Kami, he informed his other family members and associates that he had been granted some time to seek a hot-spring cure for an ailment, so none in Yamagata were aware of the plotting of Minbu. Upon his arrival, Sagami no Kami met with Minbu, and the two men took counsel together. They subsequently summoned Kuranosuke to inform him of what Lord Yoshiaki wished them to do, but upon hearing what they had to say, Kuranosuke grew pale with anger. “You may ask me to accept such a commission, but I, Kuranosuke, have no capacity for such treachery,” he retorted as he rose to his feet. In accordance with the arrangements that had been made to deal with this eventuality, a number of powerful young men quickly emerged from the adjacent chamber, confronting Kuranosuke and slaying him with their swords. “If we are slow to act, Mitsukane may hear of what has happened and attempt to escape. Let us steal into his quarters and kill him tonight.” With the two men in agreement, Minbu summoned a samurai by the name of Satake Heinai, a member of Mitsukane’s personal retinue who had regular access to his master’s home. When privately asked for his assistance, Heinai consented without demur, signing an oath that he would not betray his word. After arranging that he would leave the courtyard garden door unlatched that evening, which would allow Minbu and Sagami no Kami to gain entrance into Mitsukane’s quarters and easily slay their target, Heinai was allowed to return to his post. In the dead of night, the two men slipped into Mitsukane’s residence with their men, and they easily slew the man they had come to kill. When day broke and the news of Mitsukane’s death spread, his personal attendants and other vassals were thrown into confusion. It was then that an envoy arrived with a message from Minbu. “Mitsukane dared to rise in revolt against the Mogami clan, and for this it was decreed by Lord Yoshiaki that he would suffer the punishment of death. Kuranosuke was a party to this treachery, and yesterday, he paid for this with his life. It is fortunate, however, that Yagashiwa Sagami no Kami, an emissary of Lord Yoshiaki, has occasion to be at my residence, and I command that all of you surrender to him without delay. Any who resist will be swiftly put to death.” “What choice do we have?” Mitsukane’s men asked each other, and there was much dissent about what should be done. Yet there was no denying that Mitsukane was dead. Kuranosuke – on whom they had depended for everything – was also slain, and Minbu had turned to the other side. With no one to lead them in battle against the Mogami force or help them defend their castle, the soldiers found themselves left with no choice but to hasten to Minbu’s residence to offer themselves in surrender. The matter thus successfully concluded, Sagami no Kami returned to Yamagata Castle to give Lord Yoshiaki a detailed account of all that had passed. Greatly pleased, his lordship summoned Owari no Kami. “In this most recent affair, you have truly outdone yourself,” his lordship said, rewarding Owari no Kami with an increase in his landholdings. Soon afterwards, Minbu also arrived in Yamagata to express his gratitude to Lord Yoshiaki for the opportunity that had been given him, and he was granted his promised reward of Mitsukane’s estate of 18,000 koku. His lordship then commanded him to, “Return to Kaminoyama without delay, and find Kuranosuke’s children and kill them.” Left with no other recourse, Kuranosuke’s wife went into hiding, with a foster sister to attend to her needs, in a small hamlet of the region, where she placed Kuranosuke’s two-year-old son on her knee and mourned day and night for the fallen father of her child. However, when Minbu returned to Kaminoyama, proclaiming the concealment of Kuranosuke’s son a punishable offense and offering a rich reward to anyone with information as to his whereabouts, Kuranosuke’s wife was forced to flee the region entirely, and she sought refuge at the Anyōji Temple in Narisawa. The head priest there was a warm-hearted man who gallantly agreed to help her in her trouble, and he quietly took the child over the mountains and into Sendai, placing the child in the keeping of some kinsfolk there. The years passed, and the child grew into a man determined to seek vengeance for his father’s death. He stealthily entered Yamagata in an attempt to take Minbu’s life, but when he was foiled by Minbu’s vigilance, he sought to appease his disappointment by slaying a large number of those who had colluded with Minbu in the campaign against his father Kuranosuke. He acquitted himself most exceptionally in this exploit, and was subsequently summoned to the service of Lord Date Masamune, taking part in the Siege of Osaka where he performed several valorous feats befitting an officer of rank. However, he later became embroiled in a legal dispute with some farmers, and dismissing the arbitration of the provincial court as unjust, he left the region of Sendai. He went forth to the Kishū domain, where he took the name Satomi Kanshirō and assumed the position of his new master’s flag commissioner. At the time of this writing, he should be in his seventy-fifth or seventy-sixth year. ―――――――――――――――――――― >>CONTENTS |

|

The Extraordinary Strength of Nobesawa Noto no Kami

Lord Yoshiaki was well acquainted with the tales told of the uncommon strength of his vassal Nobesawa Noto no Kami, but one day he took it into his head to put this reputation to the test. From among his personal attendants and other retainers, he selected seven or eight of his most powerful men, and, garbed in light kimono, Lord Yoshiaki and this small band of men set off for Noto no Kami’s residence. When word of their approach reached the ears of Noto no Kami, he readied himself and went out alone into the great garden which lay outside a large room of his residence, waiting impatiently for the arrival of his guests. This took place during the seventh month, on the night of the full moon, and the scene was so flooded with moonlight that it seemed brighter even than midday. Reaching their destination, the seven or eight men accompanying Lord Yoshiaki – all of them at the peak of their physical prowess – ran quickly into the garden where Noto no Kami awaited them. When one and then another of them attempted to catch hold of Noto no Kami, he seized them with his hands and tossed them a distance of some thirteen or fourteen meters. Seeing that they were singly no match for him, the remaining four or five men set on Noto no Kami as one, surrounding him on all sides and grappling with him as they attempted to wrestle him to the ground. However, Noto no Kami had not earned his reputation for naught. He used his arms and legs to pull and fling them down easily, and then he turned on Lord Yoshiaki. The scene he had just witnessed left his lordship in no doubt that his own strength would be no match for the other man’s, and he took to his heels without even a single glance behind him. When Noto no Kami overtook him and seized him from behind, his lordship must have been at a loss for what to do, for he grabbed hold of the trunk of a withered cherry tree, some seventy-five centimeters in diameter, and held on for dear life. Noto no Kami mustered all of his strength to pull Lord Yoshiaki away from the tree, but his lordship clung even more tightly. As this powerful struggle continued, the earth surrounding the base of the tree began to give way, and the tree was suddenly wrenched from the soil, roots and all. Not even Noto no Kami had anticipated this outcome, and he released Lord Yoshiaki in his surprise. In a high good humor, his lordship addressed Noto no Kami. “Your strength far surpasses even the tales that are told of it,” his lordship said. “On that occasion when our army attempted to take Tendō while you still defended it, it is hardly surprising that you were able to sweep us up and send us packing on your own!” He bade Noto no Kami accompany him back to his castle, where he bestowed upon him many rich rewards. From that time forth, Noto no Kami was known by all the people in the domain as a man whose strength was indeed second to none. ―――――――――――――――――――― >>CONTENTS |

|

PREFACE

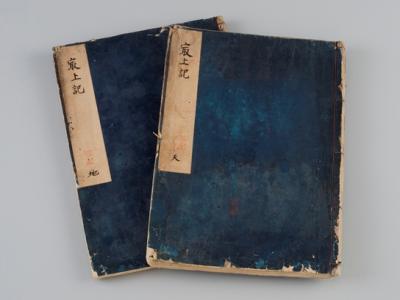

It is with great pleasure that the Yamagata City Culture Foundation presents the English translation of Saijōki: Gendaigo-yaku (Saijōki: Modern Japanese Translation, Mogami Yoshiaki Historical Museum, Yamagata City Culture Foundation, 2009). The modern Japanese translation of Saijōki is the work of Shigeo Katagiri, a historian specializing in the history of the Yamagata area and one of the foremost researchers of Mogami Yoshiaki. The original Saijōki document, written in 1634 by an unnamed former retainer of the Mogami clan, used an archaic form of Japanese that is difficult for the general reader of today to interpret, and it is thanks to the efforts of Mr. Katagiri that this work is now enjoyed by a wide range of Japanese readers. Although Mogami Yoshiaki is not nearly as well-known as Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, or other famous contemporaries, he was in reality an important daimyo of his time. Saijōki details the events in Yoshiaki’s life from the perspective of one of his own retainers, and though the events described are not always grounded in objective historical fact, this work offers the reader an eye-witness view of an important figure in the history of Yamagata. There are few works in English that contain such a detailed account of a historical personage who may be relatively unknown outside of Japan, and the completion of the English version of Saijōki on the eve of the fourth centennial of Yoshiaki’s death, which is coming up in 2014, makes the timing of this publication particularly auspicious. We hope that many readers will take advantage of this English translation to acquaint themselves with a lord known to the people of Yamagata as a wise and distinguished ruler of a bygone age. March, 2012 Noboru Ōba Yamagata City Culture Foundation, Chairman of the Board of Directors >>CONTENTS |

TRANSLATOR’S FOREWORD

Saijōki (The Mogami Chronicles) is the tale that revolves around the life of Mogami Yoshiaki (1546-1614), a damiyo of the Dewa province (present-day Yamagata prefecture) during the turbulent Sengoku, or ‘Warring States’, period that is defined by some historians as lasting from the mid-15th century to the early 17th century. A beloved figure in the history of the Yamagata region, Yoshiaki is credited for many accomplishments, including contributions to the economic development of the province, the importation of culture from the capital region, the reconstruction of Yamagata Castle, and the creation of a castle town upon which the modern city of Yamagata is based. Yoshiaki is also known as an able warrior and skilled general, and it is this aspect of his legacy that Saijōki concerns itself with. Made up of tales of his successes – and the occasional failure – in battle, this work comprises an at times loosely-connected string of the military conquests that allowed Yoshiaki to achieve his dominance over the Dewa province. Saijōki was written by a self-described former vassal of the Mogami clan in the early years of the Edo period (1603-1868), after infighting between senior Mogami clan retainers resulted in the forfeiture of the domain under the control of the Mogami family – the fifth largest domain in Japan during Yoshiaki’s lifetime – in 1622. This vassal left the Yamagata region, drifting southwards to the district of Kasai (located within the present-day Tokyo area), and it was there that he set down on paper this history of the Mogami clan. These tales should not be seen as accounts that are entirely true to history, but rather as an observer’s recollection of Yoshiaki’s life and times that is indeed based on actual events and true facts, but is also freely punctuated with the embellishments of legend and memory. Since this account does present itself as an actual history of Yoshiaki, however, it is of significant historical value in that it may serve as a valuable illustration of the status the legendary general acquired in the minds of his followers, and may also accurately reflect the stories that were told of Yoshiaki during his lifetime and the period following his death. The date given for the writing of Saijōki is 1634, and the original manuscript was written in an older style of Japanese not easily intelligible to the modern reader. To make this document accessible to a wider audience, the Mogami Yoshiaki Historical Museum commissioned the translation of the original manuscript into modern Japanese in 2009. This translation was undertaken by Shigeo Katagiri, a prominent Mogami Yoshiaki researcher as well as the Director of the Kaminoyama Municipal Library and the former Director of the Mogami Yoshiaki Historical Museum. This English version of Saijōki is a full translation of the modern Japanese version that was made while consulting the original manuscript, and I am very grateful to Mr. Katagiri and the Mogami Yoshiaki Historical Museum for their valuable help and advice. I would now like to offer a few comments and observations regarding the English translation. Firstly, I would like to note that the title – Saijōki – is a phonetic rendering of the Japanese title, which is the on-yomi (Chinese reading) of the characters “最上記”. The kun-yomi (Japanese reading) of the same three characters would be “Mogami (最上) – ki (記)”, referring to a “Mogami record” or “Mogami chronicle”, as expressed in the English title “The Mogami Chronicles”. The names of the persons who appear in Saijōki are given as they appear in the Japanese text. Often a mixture of name and title, these names, especially those of the higher-ranking personages, can be long and cumbersome. A complete list of all the persons appearing in Saijōki can be found at the end of the book, and the simpler and more commonly used designations for some of these personages are noted there. The phonetic readings of these names differ somewhat from age to age: for example, while the name “五兵衛” would have been pronounced Gohyōei in the pre-Edo period, the Edo-period reading for this name was simplified to Gohei. In this English text, the simpler Edo-period readings of names have been used. While measurements in the Japanese text appear in the form of traditional units such as ken (1.818 meters), chō (109.09 meters), and shaku (30.3 cm), I have converted these to metric amounts in the English version to allow for easier reading. On the other hand, dates are given in the era name/year number combination used in the Japanese text (for example, Enbun 1 refers to the first year of the Enbun era), while the corresponding year of the western calendar is given as a footnote. Months and days are given in a “1st day of the second month” format that may seem clumsy; however, the old Japanese calendar does not exactly correspond to the modern calendar, and the “4th day of the eighth month” would not fall on August 4 of the Gregorian calendar. It is hoped that this manner of notation will help the reader to keep this discrepancy in mind. Returning to the subject matter, it is interesting to note that while there was no single family that exerted a greater influence over the history of the Yamagata region than the Mogami clan, and no other Mogami lord who achieved the legendary status of Yoshiaki, the history contained within Saijōki (and a few differently named but almost identical versions that are clearly based on the Saijōki manuscript) remains the only definitive record of Yoshiaki’s life and achievements. The accounts of Yoshiaki’s military campaigns illustrate the tumultuous nature of the Sengoku period, and the tales are imbued with the strong warrior ethos that characterizes the samurai of this period. The time of Yoshiaki represents the zenith of the Mogami dominion over the Yamagata area, for the Edo period, which began shortly before Yoshiaki’s death, ushered in a time of peace that saw a lessening of the military role of the samurai as well as the precipitous decline of the Mogami clan. However, it is thanks to the anonymous author of Saijōki that we are still able to enjoy a vivid and personal view of the intersection between the “golden age” of the samurai and the illustrious career of the celebrated Mogami Yoshiaki. March, 2012 Lisa Somers >>CONTENTS |

(C) Mogami Yoshiaki Historical Museum

Now, also around this same period of time, there was a man named Mitsukane who occupied the region of Kaminoyama. Although married to an aunt of Lord Yoshiaki, he and his lordship were unfavorably disposed towards one another. One day, Mitsukane summoned his retainers Satomi Kuranosuke and Satomi Minbu. “As you know,” he said, “there is bad blood between myself and Yoshiaki. However, Kaminoyama is but a small territory with limited military might, and I cannot hope to challenge Yoshiaki single-handedly. It is for this reason that I have thought of Terumune of the Sendai domain. He is wed to Yoshiaki’s younger sister with two sons, but I have heard it said that he and Yoshiaki are not on good terms and do not associate with each other. If Terumune will lend us his support, I believe that we can defeat Yoshiaki. What is your opinion of this plan?”

“Your lordship’s plan is a sound one,” replied the two listening men. “If Lord Terumune will come to our aid with a large force of men, Lord Yoshiaki will undoubtedly lead his own army to Kaminoyama, where the two armies will confront each other. If we have in the meantime stationed our own troops along the mountain ridges and valleys, we can take the enemy by surprise by attacking from unexpected directions, and victory will surely be ours.”

Mitsukane was greatly pleased with this response, and he dispatched a messenger to Lord Terumune with the details of his proposal. “Although I myself have long been at odds with Yoshiaki, I have not had the capacity to challenge him alone. If you, Lord Terumune, will join my cause, I will be pleased to lead our forces in battle with a strategy that will propel us to swift victory. This will allow you to obtain the Mogami territories for your own, while I, Mitsukane, ask for but a small corner to claim as my own domain.”

Lord Terumune had in fact been privately hoping to find an ally in the Mogami inner circle for some time, and had been exploring ways in which he might take on Yoshiaki. Seeing this development as a fortuitous opportunity to further his plans, he sent a courteous letter to Mitsukane informing him that he would be arriving with his troops presently.

However, news of this plot reached the ears of Lord Yoshiaki, and he summoned an elderly warrior named Irago Sōgyū for a consultation.

“The branch castle of Narisawa is where the enemy intends to meet us in battle,” said Lord Yoshiaki. “It is my wish that you hasten to Narisawa and join forces with castle lord Narisawa Dōchū to hold the castle. The young garrison soldiers may be impatient to sally forth and do battle, but you are not to let a single one of them beyond the castle perimeter.” So commanded, Irago Sōgyū left for Narisawa Castle.

In the meanwhile, Lord Terumune came forth with his large army, and, after convening a war council, proceeded with his men to Karuisawa.

There, he summoned a local resident, questioning him in detail about the current situation within Narisawa Castle. It was after this that he spoke with Mitsukane.

“Yoshiaki has ordered Dōchū, a long-serving retainer some seventy years of age, to hold the castle, and Sōgyū, who has himself passed his sixtieth year, has been sent to lend him aid. I believe that Yoshiaki has chosen to defend the castle with these two seasoned warriors because he sees the young soldiers of the castle garrison as being inclined to impulsive action, making them vulnerable to enemy ploys and liable to bring defeat upon themselves. For Yoshiaki, this will be a fight upon familiar territory, which will give him the opportunity to hatch all manner of strategy, and I believe that he intends to send his main force to the castle at some unlooked-for moment, allowing those men to unite forces with the castle soldiers in a bid to cut us down. Furthermore, we would do well to remember the folding screen of Takeda Shingen, in the province of Kai, upon which is noted the most celebrated warriors in Japan today. Fourth on this list is the name of Irago Sōgyū, and with a warrior of this caliber holding the castle against us, capturing it will be no easy matter. If the battle goes against us, and if Yoshiaki then arrives with his great legion of soldiers to finish us off from behind, we will surely be doomed.”

Mitsukane considered what he had heard, and spoke.

“If Yoshiaki would himself come to Kaminoyama, I believed that we could gain the upper hand by concealing our soldiers in the mountains and valleys and ambushing our enemy from unexpected directions. However, Yoshiaki is a cautious man, and will most likely send forth reinforcements to a castle that lies along the route, while himself remaining prudently back. Now, if we had but a small force of men, it might be wise for us to wait for the other side to make the first move, but with a large army of this size, it seems fainthearted for us to spend needless days avoiding battle because we fear the machinations of the enemy. Better that we keep a watchful eye on the castle as we find Yoshiaki’s encampment and assail him there, and once we have triumphed over him, the castle will surely fall on its own.”

“Proceed as you see fit,” said Lord Terumune to Mitsukane, “and I will look to you to lead the attack.”

Meanwhile, in his own camp, Lord Yoshiaki had also convened a war council with Ujiie Owari no Kami, Nobesawa Noto no Kami, and other kinsmen and vassals.

Owari no Kami moved forward to speak. “From what I have gathered,” he said, “it seems that our enemy is mighty in numbers. Moreover, Mitsukane himself will be in command, and it would be unwise for us to venture deep into Kaminoyama to do battle when we have little idea of the enemy’s strategy. The enemy may choose to assail Narisawa Castle, and if this turns into a protracted battle of some five or ten days, this would be to our advantage. By dispatching our reserve army to fight alongside the castle garrison, we could turn the tide of the battle and achieve a quick victory. If the enemy instead decides to blockade the castle and venture hither to give battle, we could shift our camp to the vicinity of Mount Kashiwagi and conceal our soldiers in the woods to launch a surprise attack upon our assailants, another strategy which is sure to bring us success.”

Owari no Kami explained both these strategies in clear detail, and when the council elected to proceed with the latter option, the Mogami force marched towards Mount Kashiwagi. Soon afterwards, word arrived that the enemy had blockaded Narisawa Castle and was preparing to march on his lordship’s camp.

It was decided that they would await the enemy where they were, with Nobesawa Noto no Kami prepared to lead the vanguard, Ujiie Owari no Kami in charge of the second company, and the remaining men divided into seven units. Meanwhile, Koizumi Kamon and Katō Tarōemon were sent with 200 arquebusiers to lie in ambush on Mount Kashiwagi, under orders to listen for the drum signal that would tell them to fire upon Terumune’s hatamoto guard.

After being informed that Lord Terumune had taken up position at the foot of Mount Kashiwagi, Mitsukane led the vanguard in an attack upon Lord Yoshiaki’s encampment, and the initial skirmish between troops of the opposing armies took place in Matsubara. They fought for about an hour, but then both sides pulled back to catch their breath, and it was then that a drum signal sounded from Lord Yoshiaki’s head camp. The soldiers who had been lying in ambush were on their feet in an instant and eagerly rushing down towards the foot of the mountain; there, with the flank of Lord Terumune’s head camp in their sights, they rained a hail of bullets down upon the enemy with their 200 arquebuses. This unexpected attack threw Lord Terumune’s hatamoto retainers into confusion, and the soldiers behind them prepared to flee without any attempt at resistance. Into this melee swooped Nobesawa Noto no Kami, iron baton in hand, with Suda Kojūrō following strongly behind, and Noto no Kami’s men unhesitatingly followed their leader into battle, as did the second company under Ujiie Owari no Kami. Abandoning their battle formations in their eagerness to engage the enemy soldiers, they fought with such raw will and fierce determination that the enemy army was utterly overwhelmed. Soldiers of the van and rear guards fell back in a single mass to flee, only to be pursued and slain by Lord Yoshiaki’s men. So relentless was the Mogami assault that the position of Lord Terumune himself appeared to be in peril, but his long-serving fudai(1) retainers turned back en masse to protect their master, and, with one and then another of them falling in his defense, they finally succeeded in reaching the outermost moat of Kaminoyama Castle.

In the midst of these developments, Lord Terumune’s wife also arrived at the castle in a palanquin.

“Of late, I had wondered whither you ventured to give battle,” she said to Lord Terumune, “only to learn of this war taking place between brothers.

What manner of behavior is this? When my father, Lord Yoshimori, lay on his deathbed, he summoned you, Lord Terumune, to his side and bade you always behave as a friend to Yoshiaki. In time, your young son, Masamune, will come of age, and if our clans remain bound by the closest of familial ties, the Uesugi and Satake families might ally themselves together and seek to overcome us, but we would still have naught to fear. It was but recently that my father called on the Date family and retainers to respect the wishes of Yoshiaki, and on the Mogami side to consider well how their actions might affect you, Terumune, commanding both sides to give due deliberation to the other – but can it be that you have both so quickly forgotten his words and taken up arms against one another? How shameful! I entreat you to withdraw your army at once. If you will not agree, I beg that you strike me down with your sword and kill me now.” Terumune’s wife wept as she appealed to her husband.

In his heart, Terumune had been secretly desirous of someone who would compel him to desist and offer him the opportunity to withdraw his forces, and he welcomed the mediation of his wife. “Speak likewise to Yoshiaki,” he said, returning to Yonezawa before dawn the following day.

――――――――――――――――――――

(1) Retainers whose families had served a lord for many generations

>>CONTENTS